Un cuento de Navidad/A Christmas tale

Ahora que se acercan las navidades y parece que hay más niños que nunca, un guiño a todos los colegios que nos visitan. Siempre los recibimos con la leyenda del Ginkgo biloba. El árbol de las mariposas.

Hace millones de años, los árboles andaban corriendo por el monte. Se sentían libres y poderosos. Un día los árboles más grandes desafiaron al viento. El viento enfadado soplo con fuerza y hubo una gran batalla. Los árboles se agarraban al suelo como podían, sus ramas se doblaban y volaban hojas por todas partes. En medio de la batalla cruzó una bandada de mariposas. Cuando estaban a punto de ser arrastradas por el viento, el Ginkgo biloba corrió al centro del valle y extendió sus ramas para que se agarraran a ellas. La batalla terminó y las mariposas sobrevivieron agarradas al Ginkgo.

Después de la batalla; de tanto agarrarse al suelo, los árboles ya no pudieron moverse; les habían salido raíces y donde estaban se quedaron. Algunos de los árboles se quedaron sin hojas, empezaron las estaciones. Al llegar la primavera, a los árboles que se habían quedado desnudos, les salieron las hojas de nuevo. A todos menos al Ginkgo, que, al haber estado en lo peor de la batalla nunca volvieron a salirle hojas. Estaba en el centro del valle, desnudo. Las mariposas en agradecimiento volaron a sus ramas para vestirlo, volaron cada día durante cien años, hasta que una mañana al volar hacia él, se dieron cuenta de que le habían salido hojas en forma de mariposa.

Now that Christmas is approaching and there seem to be more children than ever, a special wink to all the schools that visit us. We always welcome them with the legend of the Ginkgo biloba, the butterfly tree.

Millions of years ago, trees were running around the mountains. They felt free and powerful. One day the biggest trees defied the wind. The angry wind blew hard and there was a great battle. The trees clung to the ground as best as they could, their branches bent and leaves flew everywhere. In the midst of the battle a flock of butterflies flew across. As they were about to be swept away by the wind, the Ginkgo biloba ran to the centre of the valley and stretched out its branches for them to cling to. The battle was over and the butterflies survived clinging to the Ginkgo.

After the battle, from holding on to the ground, the trees could no longer move; they had grown roots and stayed where they were. Some of the trees became leafless, the seasons began. When spring came, the trees that had been left bare sprouted leaves again. All except the Ginkgo, which, having been in the worst of the battle, never grew leaves again. It stood in the centre of the valley, naked. The butterflies in gratitude flew to its branches to dress it, they flew every day for a hundred years, until one morning when they flew to it they noticed that it had grown leaves in the shape of a butterfly.

Horror vacui

El otro día escuche a alguien la expresión “horror vacui” refiriéndose a una exposición en la que no quedaba un centímetro de pared libre. Pensé en el jardín, en como ahora con los árboles sin hojas parece más vacío. Y no solo pienso en la forma de exponer, pienso en la filosofía de la colección, en lo que hay detrás.

El miedo al vacío parece ser una epidemia en nuestros días, miedo a la falta de imágenes, miedo a la pausa, miedo al silencio. Somos la sociedad del ruido en todos los sentidos. Se da por hecho la falta de verdad, la falta de contenido y la necesidad de llenar ese vacío de lo que sea.

Aquí no. Aquí necesitamos silencio para escuchar, vacío para ver y tiempo…mucho tiempo.

The other day I heard someone use the expression ‘horror vacui’ referring to an exhibition in which there wasn’t an inch of wall free. I thought of the garden, of how now with the trees without leaves it seems emptier. And I don’t just think about the way of exhibiting, I think about the philosophy of the collection, about what lies behind it.

Fear of emptiness seems to be an epidemic nowadays,

fear of the lack of images, fear of pause, fear of silence. We are a society of noise in every sense. We take for granted the lack of truth, the lack of content and the need to fill that emptiness with anything.

Not here. Here we need silence to listen, emptiness to see and time… a lot of time.

Temporada de exposiciones/Exhibition season

En invierno los árboles descansan; es el momento perfecto, la temporada para sacarlos del jardín y llevarlos a otros lugares. Esta semana viajamos a conocer uno de esos lugares donde poder enseñarlos a un público nuevo.

Exposiciones tan especiales como las que hicimos en Ivory Press en Madrid, Museo San Telmo de San Sebastián o el Centro de arte de Alcobendas; nos dieron muchas alegrías. En ellas los árboles cumplieron como nunca su misión de emocionar y sorprender, con esa concentración que tienen de vida, arte, naturaleza y tiempo.

Si las exposiciones y congresos de bonsái tradicionales han sido, son y serán siempre nuestro lugar amigo, donde la colección se encuentra con viejos conocidos que la aprecian, en estos nuevos lugares la conexión con el público es muy distinta. ¿Qué siente alguien la primera vez que ve uno de los árboles?

Es como cuando alguien no ha visto tu película favorita o no ha leído un libro que a ti te emocionó y sientes envidia por lo que le queda por disfrutar.

Pues eso, a todos los viejos conocidos y a los nuevos; empieza la temporada…

In winter the trees rest; it is the perfect time, the season to take them out of the garden and take them to other places. This week we travelled to see one of those places where we could show them to a new audience.

Exhibitions as special as the ones we did at Ivory Press in Madrid, Museo San Telmo in San Sebastián or the Centro de Arte de Alcobendas, gave us a lot of joy. In them the trees fulfilled as never before their mission to thrill and surprise, with that concentration of life, art, nature and time that they have.

If the traditional bonsai exhibitions and congresses have been, are and will always be our friendly place, where the collection meets old acquaintances who appreciate it, in these new places the connection with the public is very different: What does someone feel the first time they see one of the trees?

It’s like when someone hasn’t seen your favourite film or read a book that moved you and you feel envious of what they have yet to enjoy.

So, to all the old acquaintances and the new ones; the season starts…

Marcescencia/Marcescence

Esta semana vino a vernos Patxi; dejó el grandioso otoño de Irati para venir a ver el nuestro, algo más pequeño.

Y es que, si ya casi todos los caducos han perdido sus hojas, las hayas y los robles se empeñan en mantenerlas. Es el enigmático fenómeno de la marcescencia, un fenómeno por el cual algunos árboles retienen sus hojas en las ramas durante todo el invierno. Hay varias teorías para explicarlo; que mantienen las hojas para proteger de las heladas las yemas del año siguiente o para proteger las ramas y los brotes del ramoneo de los animales, ya que las hojas secas tienen mal sabor. También se especula con que, al desprenderse de las hojas en primavera, el árbol libera al suelo los nutrientes que contienen justo cuando más los necesita. Sea cual sea el motivo….

Caminar por la selva de Irati, en Navarra,

al final del invierno, con las hojas

marcescentes cubriendo ya el suelo y

reflejando la luz declinada del atardecer,

produce un sentimiento indefinible

“a los pinos el viento”

Luis Vallejo

This week Patxi came to see us; he left the great autumn of Irati to come and see ours, a little smaller.

And the fact is that, if almost all the deciduous trees have already lost their leaves, the beech and oak trees insist on keeping them. It is the enigmatic phenomenon of marcescence, a phenomenon by which some trees retain their leaves on their branches throughout the winter. There are several theories to explain it, that they keep the leaves to protect the following year’s buds from frost or to protect the branches and shoots from being browsed by animals, as dry leaves have a bad taste. There is also speculation that by shedding the leaves in spring, the tree releases the nutrients they contain into the soil just when it needs them most. Whatever the reason….

Walking through the Irati rain forest in Navarre,

in the late winter, with the marcescent leaves now

covering the ground and reflecting the fading light

of dusk, arouses an undefinable feeling.

The Wind among the Leaves

Luis Vallejo

Otoño amarillo/Yellow autumn

Viendo esta fotografía de Luis, y el glorioso otoño del “Arakawa”; me pregunto por la diferencia entre el otoño de nuestros bosques europeos, y sus tonalidades amarillas frente al de los bosques de Norteamérica y Oriente y sus tonalidades mucho más rojas.

Leyendo sobre el tema, descubro datos muy interesantes…para empezar tenemos el proceso por el que pasan los árboles; …en otoño todo está cansado, los árboles dejan de producir clorofila que da el color verde a las hojas y están pierden color, empiezan a verse otros pigmentos (los carotenoides) que les dan el color amarillo y ocre. Resulta que los árboles de otras latitudes cuando llega el otoño empiezan a producir otro pigmento, que es rojo y protege al árbol de insectos, (como siempre, el rojo es señal de peligro) y aquí la pregunta del principio; ¿porque unos producen el nuevo pigmento y los otros no?

Al parecer es una cuestión evolutiva; los árboles europeos dejaron de defenderse. Las cadenas montañosas europeas (las principales) discurren de este a oeste mientras que en America y Asia van de norte a sur. Por lo que he podido entender, los insectos en Europa no pudieron emigrar al sur cuando hubo frío extremo (se lo impedían las montañas) y quedaban atrapados en el hielo. Sin insectos los árboles dejaron de producir el pigmento, mientras que en América los insectos corrían felices al sur…y sus árboles cada vez más rojos…

Me surgen mil preguntas nuevas; ¿ necesitamos más insectos? …

Seeing this photograph of Luis, and the glorious autumn of the ‘Arakawa’; I wonder about the difference between the autumn of our European forests, and its yellow tones versus that of the forests of North America and the East and their much redder tones.

Reading up on the subject, I discover very interesting facts…to begin with we have the process that trees go through; …in autumn everything is tired, the trees stop producing chlorophyll that gives the green colour to the leaves and they lose colour, other pigments (the carotenoids) start to be seen and give them the yellow and ochre colour. It turns out that trees in other latitudes when autumn arrives begin to produce another pigment, which is red and protects the tree from insects, (as always, red is a sign of danger) and here is the question at the beginning; why do some trees produce the new pigment and others do not?

It seems to be an evolutionary question; European trees stopped defending themselves. The European mountain ranges (the main ones) run from east to west while in America and Asia they run from north to south. As far as I have been able to understand, insects in Europe could not migrate south when there was extreme cold (prevented by the mountains) and were trapped in the ice. Without insects the trees stopped producing pigment, while in America the insects happily ran south…and their trees got redder and redder…

A thousand new questions come to mind; do we need more insects?

Los árboles que esperan/The waiting trees

Entre las personas que nos visitan, hay algunas que son capaces de apreciar la singularidad y la belleza de algunos de los árboles.

Estas personas únicas, son capaces de ver lo que Luis vio en ellos. Ejemplares que no vienen de un renombrado vivero en Japón o igual si… algunos son hallazgos fortuitos; encontrados en el campo, en un vivero, un regalo inesperado…

No se trata de bonsáis convencionales que puedan explicarse según las normas, cada uno de ellos tiene algo especial. Son los árboles que esperan. Pasan inadvertidos gran parte del año, esperando en distintos puntos del vivero. Son como esos ciervos, trineos y elfos de luces que si te fijas bien ya están por todas partes; agazapados en la oscuridad de las rotondas esperando al pistoletazo de salida de la Navidad para que todos podamos verlos.

Estos árboles singulares tienen a lo largo del año su momento estelar; el momento en que todos pueden verlos, un otoño rabioso, una primavera llena de flores o un verano exuberante. Hoy un pequeño homenaje a todos ellos. Hoy es Navidad.

Among the people who visit us, there are some who are able to appreciate the uniqueness and beauty of some of the trees.

These unique people are able to see what Luis saw. Specimens that do not come from a renowned nursery in Japan or maybe they do… some are random discoveries; found in the countryside, in a nursery, an unexpected gift…

These are not conventional bonsai that can be explained according to the rules. They are the trees that are waiting. They go unnoticed most of the year, waiting in different parts of the nursery. They are like those deer, sleighs and light elves that if you look closely are already everywhere; crouched in the darkness of the roundabouts waiting for the starting pistol of Christmas so that we can all see them.

Throughout the year these singular trees have their special moment; the moment when everyone can see them, a raging autumn, a spring full of flowers or an exuberant summer. Today a small tribute to all of them. Today is Christmas.

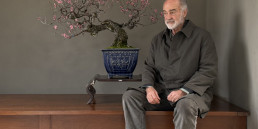

Presentación del libro de Luis Vallejo “a los pinos el viento” en Washington D.C. el pasado 5 de octubre del 2023, con la presencia del Embajador de España en Estados Unidos; Santiago Cabanas, Director adjunto de la National Gallery of Art, Eric L. Motley, Director del U.S. National Arboretum, Richard Ollsen y representantes de la Embajada de Japón en Estados Unidos. Interesante coloquio entre el autor y los asistentes de las distintas instituciones y el fotógrafo Fernando Maquieira.

Gracias a todos los que pudieron acompañarnos y a todos los que han participado en el proyecto desde España.

Presentation of Luis Vallejo’s book «The Wind among the Leaves» in Washington, D.C., on October 5, 2023, with the presence of the Spanish Ambassador to the United States; Santiago Cabanas, Deputy Director of the National Gallery of Art; Eric L. Motley, Director of the U.S. National Arboretum; Richard Ollsen; and representatives of the Embassy of Japan in the United States. An interesting discussion was held between the author and attendees from the various institutions, along with photographer Fernando Maquieira.

Thanks to everyone who was able to join us and to all those who participated in the project from Spain.

Los espacios inmutables/The immutable spaces

Esta semana leía un artículo sobre el cierre del mítico café Gijón de Madrid y sobre la necesidad de tener espacios inmutables; esos lugares donde todo permanece igual, excepto tu cada vez que regresas.

En el jardín se produce algo parecido, es el mismo jardín que se inauguró hace ya treinta años. El recorrido, la entrada, nuestro pequeño taller, el estanque, el banco bajo el tilo…

Los incondicionales del jardín, que vuelven varias veces al año, deben sentir eso, todo sigue igual, pero son treinta años y ellos van cambiando.

No es que el jardín no cambie; el paso del tiempo es evidente, los árboles son más viejos y algunos muros tienen una pátina que ha dejado ya muy atrás al espíritu wabi sabi. Es el concepto el que no cambia, no sucumbe a las modas ni a las demandas del mundo exterior.

Ahora que vivimos nuestro propio momento de cambio/ampliación/nuevo proyectoilusionante…te planteas si no tendrás algún día nostalgia de lo que un día fue.

This week I was reading an article about the closure of the mythical café Gijón in Madrid and about the need to have immutable spaces; those places where everything remains the same, except you every time you return.

In the garden something similar happens, it is the same garden that was inaugurated thirty years ago. The path, the entrance, our little workshop, the pond, the bench under the lime tree…

The garden’s devotees, who come back several times a year, must feel that, everything remains the same, but it is thirty years and they are changing.

It is not that the garden does not change; the passage of time is evident, the trees are older and some walls have a patina that has left the wabi sabi spirit far behind. It is the concept that does not change, does not succumb to fashions or the demands of the outside world.

Now that we are living our own moment of change/expansion/exciting new project… you wonder if you will not one day be nostalgic for what it once was.

El junípero de Kimura

En la colección hay algunos árboles ejemplares y este es sin duda uno de ellos. Pocas veces ha estado en el tokonoma, ya que tiene un lugar de honor presidiendo la exposición, pero este mes Mario ha estado trabajándolo y aprovechamos para hacerle una foto con Luis. Llevan juntos muchos años, es uno de esos árboles con los que tiene una conexión especial.

Lo que mas llama la atención es su tronco, su vejez…dicen que tiene 300 años, cada vez que lo digo me acuerdo de la anécdota sobre un esforzado guía de museo, que en sus explicaciones sumaba a la edad de la obra, los días que llevaba trabajando e informaba al público con precisión suiza; ..»esta vasija tiene tres mil años, dos meses, tres semanas y un día…»

Es uno de esos árboles que tienen la capacidad de transportarnos, de conectarnos con la naturaleza. A los que somos de estos lares, nos lleva a pensar en lugares como el Sabinar de El Hierro y a quienes no conocen ese maravilloso lugar, les hace pensar en otros lugares únicos, con sabinas o juníperos expuestos durante años a los elementos.

Nosotros nos referimos a él como “el junípero de Kimura”, tenemos varios juníperos del gran Masahiko Kimura, pero solo a este le llamamos así. Aquí es el junípero de Kimura por excelencia.

There are some exemplary trees in the collection, and this is certainly one of them. It has rarely been in the tokonoma, as it has a place of honour presiding the exhibition, but this month Mario has been working on it and we took the opportunity to take a photo of it with Luis. They have been together for many years, It is one of those trees with which he has a special connection.

What is most striking is its trunk, its old age… they say it is 300 years old, every time I say it I am reminded of the anecdote of a hard-working museum guide who, in his explanations, would add to the age of the piece the days he had been working and inform the public with swiss precision: ‘This pot is three thousand years, two months, three weeks and one day old…’.

It is one of those trees that has the ability to transport us, to conect us with nature. For those of us who are from these parts, it makes us think of places like el Sabinar de El Hierro and for those who don’t know this wonderful place, it makes them think of another unique place with junipers or sabinas exposed to the elements.

We refer to it as ‘Kimura’s juniper tree’, we have several junipers by the great Masahiko Kimura, but only this one is called that. Here it is the Kimura juniper par excellence.

Otoño/Autumn

Este texto era obligado, nuestra temporada más esperada.

El otoño es el último esfuerzo antes de que todos descansemos durante el invierno, dejamos atrás los trabajos de todo el año…los trasplantes del principio del año, la actividad frenética de la primavera, la pelea del verano…tanto tiempo con los árboles hace que nos identifiquemos con ellos.

Si el verano nos ha dejado agotados, ahora todos (árboles y cuidadores) estamos mejor, nuestro aspecto es mejor y tenemos más energía. No ha empezado el frío y nos pasamos el día mirando al cielo, hoy por fin han llegado las primeras lluvias y han pasado grullas en dirección al sur. El otoño ya está aquí.

El jardín empieza esa temporada en la que se divide en dos; el jardín que no cambia, las coníferas que lucen ahora más verdes que en verano y el otro jardín el que va cambiando de color y perdiendo sus hojas cada vez que hay algo de viento.

Como todavía no han otoñado uso las fotos de Fernando Maquieira para ilustrar este texto y lo que está por venir

This text was a must, our most awaited season.

Autumn is the last effort before we all rest for the winter, we leave behind the work of the whole year…the transplanting at the beginning of the year, the frenetic activity of spring, the fight of summer…so much time with the trees makes us identify with them.

If the summer has left us exhausted, now we all (trees and caretakers) are better, we look better and we have more energy. The cold has not yet started and we spend the day looking at the sky, today the first rains have finally arrived and a group of cranes have passed by heading south. Autumn is already here.

The garden is full of people, it is the beginning of that season when it is divided in two; the garden that does not change, the conifers that look greener now than in summer and the other garden that is changing its color and losing its leaves every time there is some wind.

As it is not yet autumn, I use Fernando Maquieira’s photos to illustrate this text and what is about to come.

Babia

Ayer estuve en la inauguración de la librería de una amiga. La ha llamado Babia.

A inaugurarla acudieron tres personajes de la literatura y el arte; Julio Llamazares, Jesus Marchamalo y Antonio Santos. Hablaron de libros, de arte… y del nombre de la librería, que tiene que ver con el lugar geográfico (por la conexión de mi amiga con León) y por la expresión “estar en Babia”.

Julio Llamazares, que también es de León, explico su origen, de cómo los pastores de allí cuando estaban en trashumancia, lejos de esa tierra tan bonita, se quedaban mirando nostálgicos el fuego por las noches y alguien siempre decía; eh! que estas en Babia…dijo entonces algo que me encantó; estar en Babia es cuando tu cuerpo esta en un lugar y tu alma en otro, igual que cuando lees.

Con su charla, me dejaron pensando en lo importante que es poder salir a veces de la realidad más acuciante simplemente abriendo un libro, viendo una película, admirando un cuadro o un bonsái, escuchando una canción o paseando por un jardín como este. Ese es el sentido último del arte, lo que hace que sea imprescindible.

Me acordé de una conversación reciente con alguien que se dedica también a temas poco prácticos… dudaba, se preguntaba como podían convivir rutinas tan diferentes; uno que se despierta y prepara un jardín, uno que escribe o pinta y otro que se prepara para operar en un quirófano o para salvar vidas en algún lugar del mundo. Ayer estando en Babia lo vi clarísimo.

Yesterday I was at the opening of a friend’s bookshop. The name of the bookshop is Babia.

The opening was attended by three literary and artistic personalities: Julio Llamazares, Jesus Marchamalo and Antonio Santos. During the talk they spoke about books, art…and the name of the bookshop, which has to do with the geographical location (because of my friend’s connection with León) and the expression ‘estar en Babia’ (to be in Babia).

Julio Llamazares, who is also from León, explained its origin, how the shepherds there, when they were in transhumance, far from that beautiful land, would stare nostalgically at the fire at night and someone would always say; hey, you are in Babia…he then said something that I loved; to be in Babia is when your body is in one place and your soul is in another, just like when you read.

I kept thinking about how important it is to be able to escape sometimes from the most pressing reality by simply opening a book, watching a film, admiring a painting or a bonsai, listening to a song or strolling through a garden like this one. That is the ultimate meaning of art, what makes it indispensable.

I remembered a recent conversation with someone who is also dedicated to impractical subjects… he doubted, he wondered how such different routines could coexist, one who wakes up and prepares a garden, one who writes or paints and another who is preparing to operate or to save lives somewhere in the world. Yesterday when I was in Babia I saw it very clearly.