Goteras/Leaks

Esta semana hemos tenido el rodaje de un anuncio en el jardín. No es nuestro primer rodaje, nos adaptamos a los tiempos, hay que diversificar, conseguir formas de financiación fuera de la actividad principal y poco rentable de un museo. Museos interactivos, mediáticos, pensados para eventos, rodajes, restaurantes y experiencias. No es ningún secreto que como negocio un museo pequeño y privado puede ser una ruina si solo tiene arte…

¿Pero y los grandes museos? al parecer el Louvre, el museo más visitado del mundo tiene goteras, problemas estructurales, dificultades de personal y notorios fallos de seguridad.

El Louvre, con financiación pública y 9 millones de visitantes al año, tiene en marcha el proyecto «Nuevo renacer» para adaptarlo a los tiempos, se enfrenta a una montaña de inversiones y no tiene los fondos para acometerlas.

Mientras encontramos nuestro camino nos consuela tener algo en común con él, también tenemos goteras, montañas de inversiones y algo de arte…

This week we have had the shooting of an advertisement in the garden. It is not our first filming, we are adapting to the times, we have to diversify, to find ways of financing outside the main and not very profitable activity of a museum. Interactive museums, mass media, designed for events, filming, restaurants and experiences. It is no secret that as a business a small, private museum can be a ruin if it only has art…

But what about the big museums? Apparently the Louvre, the most visited museum in the world, has leaks, structural problems, staffing difficulties and notorious security failures.

The Louvre, with public funding and 9 million visitors a year, has the «New Renaissance» project underway to adapt it to the times, faces a mountain of investment and does not have the funds to undertake it.

While we find our way, we take comfort in the fact that we have something in common with it, we also have leaks, mountains of investments and some art…

Otras publicaciones

un bosque

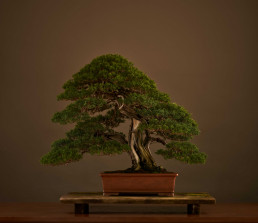

En la colección tenemos muchos bosques de muy distintas especies. Cada uno es un mundo; no solo porque entre si son muy diferentes si no porque son en si un micro mundo. Tienen una presencia muy diferente a la de un ejemplar solitario.

Existen estudios muy interesantes sobre como interactúan los bosques en la naturaleza, como sus conexiones entrelazadas por el suelo le hacen capaces de colaborar y comunicarse. Si siempre se pensó que los árboles de un bosque competían por los recursos; nutrientes, agua, luz…estos estudios hablan de que en realidad los comparten, hablan de individuos que se relacionan.

Parece que no solo comparten nutrientes; son capaces de comunicarse y avisar de plagas o amenazas. Cuentan que una arboleda de acacias en Africa aumentó la toxicidad de sus hojas cuando los antílopes se comieron las hojas de sus árboles periféricos.

…pero eso ya lo sabía Mario Benedetti:

El bosque crea

nidos, juncos, en fin

vocabulario.

In the collection we have many forests of very different species. Each one is a micro world. They have a very different presence from a single specimen.

There are very interesting studies on how forests interact in nature, how their intertwined connections through the soil make them able to collaborate and communicate. If it was always thought that the trees in a forest competed for resources; nutrients, water, light… these studies show that they actually share them, they talk about individuals that relate to each other.

But it seems they not only share nutrients; they are able to communicate and warn of pests or threats. It is said that an acacia grove in Africa increased the toxicity of its leaves when antelopes ate the leaves of its peripheral trees.

…but Mario Benedetti already knew that:

The forest creates nests

bulrushes in short

vocabulary.

Otras publicaciones

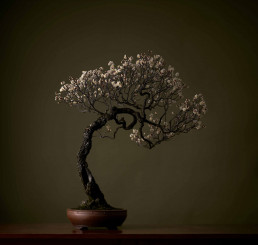

Giacometti

“Una exposición de Giacometti es un pueblo. Esculpe unos hombres que se cruzan por

una plaza sin verse; están solos sin remedio y, no obstante, están juntos”. Jean Paul Sartre

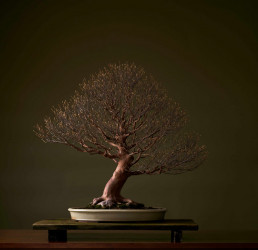

Estos días de invierno los árboles descansan expuestos a la intemperie, su presencia se intuye mientras recorres el jardín, la lluvia los hace todavía más presentes, más visibles. Cada uno en su pedestal, solos y sin embargo como en la exposición de Giacometti; juntos.

Mas que en ninguna otra estación, durante el invierno, son más escultura que árbol y el jardín, sin las distracciones de otras estaciones, es más exposición que jardín.

«An exhibition by Giacometti is a village. He sculpts men crossing each other’s paths in a a square without seeing each other; they are hopelessly alone and yet they are together». Jean Paul Sartre

These winter days the trees rest exposed to the elements, their presence is sensed as you walk through the garden, the rain makes them even more present, more visible. Each one on its own pedestal, alone and yet, as in Giacometti’s exhibition, together.

More than in any other season, during the winter, they are more sculpture than tree and the garden, without the distractions of other seasons, is more exhibition than garden.

Otras publicaciones

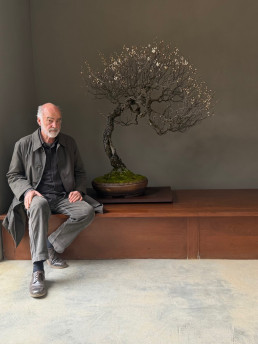

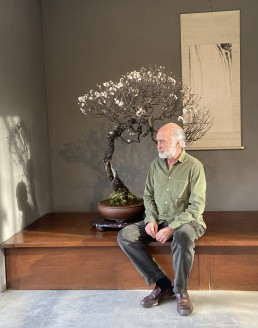

Luis y el ume

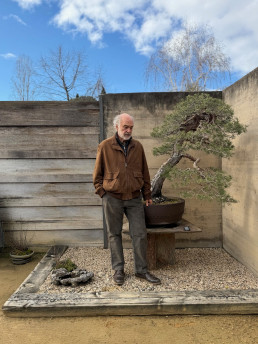

Ayer durante un rato salió el sol, el tiempo justo para hacer esta foto.

El Tokonoma de febrero no puede estar dedicado a otro árbol. El ume que vino del jardín de Sinji Suzuki; uno de los árboles más especiales de la colección y uno de los preferidos de Luis.

Hace tiempo que empezamos la tradición de fotografiarles juntos por su cumpleaños y con el tiempo parece como si se hubieran sincronizado, el ume no florece hasta que llega el cumpleaños de Luis. Los otros dos prunus mume de la colección ya perdieron la flor.

Algunos dicen que es la variedad, la edad, el lugar del jardín en el que está…yo prefiero pensar que existe un vínculo invisible entre ellos y que el ume espera todos los años para felicitar a Luis con sus flores.

Hoy todavía Luis no ha llegado, así que aquí está esperándolo.

Yesterday the sun was out for a while, just long enough to take this photo.

February’s Tokonoma could not be dedicated to any other tree.The ume that came from the garden of Sinji Suzuki; one of the most special trees in the collection and one of Luis’ favourites.

Some time ago we started the tradition of photographing them together for his birthday and over the years it seems as if they have synchronised, the ume does not flower until Luis’s birthday arrives. The other two prunus mume in the collection have already lost their flowers.

Some say it is the variety, the age, the place in the garden where it is… I prefer to think that there is an invisible link between them and that the ume waits every year to congratulate Luis with its flowers.

Today Luis hasn’t arrived yet so here he is waiting for him.

Otras publicaciones

Un hayedo en un pinar

Las fotografías son de la exposición que hemos llevado al congreso UBE en Aranjuez.

Las colecciones están hechas para exponerse, nosotros tenemos la suerte de tener un lugar, un jardín donde enseñarla, pero también nos encanta llevarla a otros lugares y que puedan verla muchas más personas.

Hemos estado en galerías de arte, museos, palacios de congresos y todo tipo de espacios. Y el reto siempre es saber exponer de manera que los árboles transmitan su esencia y sean capaces de transportarnos a un lugar muy alejado de donde están.

Cuando estas acostumbrado a un espacio como el nuestro, en el que los árboles parecen haber encontrado su lugar perfecto, acompañados de plantas, agua y piedras, es fácil caer en la tentación de llevarse el jardín también…

¿Quién ha visto sin temblar

un hayedo en un pinar?

Las encinas

Antonio Machado

The pictures are from the exhibition we took to the UBE Congress in Aranjuez.

The collections are made to be shown, and we’re lucky to have a place, a garden, where we can display it, but we also love taking it to other places so that many more people can see it.

We’ve been to art galleries, museums, convention centres, and all kinds of spaces. The challenge is always to know how to exhibit them in such a way that the trees convey their essence and are able to transport us to a place far away from where they are.

When you are used to a space like ours, where the trees seem to have found their perfect place, accompanied by plants, water and stones, it is easy to be tempted to take the garden with you too…

Who has seen, without trembling,

A beech grove, amid a pine forest?

Antonio Machado

Otras publicaciones

Los tres amigos del invierno/ The three friends of winter

En Japón los tres amigos del invierno son el pino, el bambú y el prunus mume (albaricoquero de flor, conocido en Japón como ume). Aquí nuestros tres amigos en estos días son los tres prunus mume en flor. Sobre el ume se dice que representa la humildad en condiciones adversas y el triunfo de la virtud sobre las dificultades. Es un árbol que florece durante el invierno, y trae la esperanza de que pronto llegará la primavera. Con ellos esta semana tenemos un Tokonoma especial que perfuma la entrada al jardín.

Para completar la fiesta de los ume, hemos plantado un gran ejemplar en el jardín, es un esqueje de unos quince años del mume más conocido de nuestra colección. Un árbol muy viejo que vino hace ya muchos años del vivero de Sinji Suzuki. Hace algún tiempo nos planteamos hacerle una reproducción en bronce, ya que se trata de un árbol muy especial. Quizás un día la hagamos, pero de momento ya tenemos una parte suya en el jardín.

Esta fiesta dura lo que aguanten sus flores, aquí os esperamos

In Japan the three friends of winter are pine, bamboo and prunus mume (flowering apricot, known in Japan as ume). Here our three friends these days are the three flowering prunus mume. The ume is said to represent humility in adverse conditions and the triumph of virtue over hardship. It is a tree that blooms during the winter, and brings hope that spring will soon come. With them this week we have a special Tokonoma that perfumes the entrance to the garden.

To complete the ume party, we have planted a large specimen in the garden, a fifteen year old cutting of the best known mume in our collection. A very old tree that came many years ago from Sinji Suzuki’s nursery. Some time ago we considered making a bronze reproduction of it, as it is a very special tree. Maybe one day we will do it, but for the moment we already have a part of it in the garden.

This party lasts as long as the flowers resist, we are waiting for you here.

Otras publicaciones

Arte y Ciencia/Art and Science

A esta pequeña sabina la llamamos “el Tirabuzón”; el dibujo lo hizo Luis y es la portada de su libro “a los pinos el viento”. La foto es de Fernando Maquieira.

Hablando de libros, el otro día me recomendaron uno sobre plantas. Uno de esos tesoros que te sorprenden.

Juniperus sabina…

…Los juníperos son una especie longeva que crece en lo alto de la montaña en suelos calizos, esqueléticos. Sus ramas rastreras son nodrizas de otras especies leñosas, convive con el berberis, los espinos, las rosas, las aulagas, los tomillos y otros arbustos de la familia, como los enebros y las sabinas…

…Los juníperos poseen sabinol, una sustancia con propiedades anticonceptivas, emanogogas y abortivas aunque, tomadas en el momento correcto, tienen la virtud de facilitar el parto…

María del Carmen Tostado. Álbum de Plantas Prohibidas

Un catálogo de plantas prohibidas, con poemas, dibujos y fichas botánicas en el que combina el conocimiento científico y el arte. Pienso en el concepto del que habla Luis siempre; la trasversalidad en el arte, como todas las disciplinas; la literatura, la poesía, la escultura, la pintura, la arquitectura, el paisajismo… están interconectadas, y el bonsái como ejemplo perfecto de esa conexión entre el arte y la ciencia.

We call this little juniper ‘el Tirabuzón’; the drawing was made by Luis and is the cover of his book ‘a los pinos el viento’. The photo is by Fernando Maquieira.

Speaking of books, the other day I was recommended one about plants. One of those treasures that surprise you.

Juniperus sabina…

…Junipers are a long-lived species that grows high up in the mountains in limestone, skeletal soils. Its creeping branches are the nurse of other woody species, it coexists with berberis, hawthorns, roses, gorse, thyme and other shrubs of the family, such as junipers and savins…

…Junipers possess sabinol, a substance with contraceptive, emanogogue and abortive properties although, taken at the right time, they have the virtue of facilitating childbirth…

Maria del Carmen Tostado. Album of Forbidden Plants

A catalogue of forbidden plants, with poems, drawings and botanical information, combining scientific knowledge and art.. I think about the concept Luis always talks about; the transversality in art; how all disciplines; literature, poetry, sculpture, painting, architecture, landscaping… are interconnected, and bonsai as the perfect example of the connection between art and science.

Otras publicaciones

Edad/Age

Matusalén es un pino torcido de 4.857 años, es uno de los árboles vivos más viejos del mundo y está en algún lugar del Bosque Nacional Inyo en California. La dirección exacta no la dan para que no corra con la misma suerte que su hermano mayor, un pino llamado Prometeo, que fue talado por un estudiante de geografía…

En la colección tenemos algunos árboles muy viejos. La edad de los árboles es un tema fascinante, nos gusta hablar de ella de la misma manera que hablamos de la nuestra; árboles jóvenes, maduros, viejos…pero no es lo mismo, los árboles tienen una longevidad potencial extraordinaria, se renuevan, sus brotes son siempre jóvenes. No importan los años.

Un árbol muere por factores externos mucho antes de que pueda haber un declive por su edad. Por eso los árboles más viejos en la naturaleza son ejemplos a estudiar, los que tienen más capacidad de adaptación y resistencia. Son los que han conseguido sobrevivir a los cambios en un mundo que no para de cambiar.

Methuselah is a 4,857-year-old twisted pine, one of the oldest living trees in the world, somewhere in the Inyo National Forest in California. The exact address is not given so that it does not suffer the same fate as its older brother, a pine tree called Prometheus, which was chopped down by a geography student…

In the collection we have some very old trees. The age of trees is a fascinating subject, we like to talk about it in the same way we talk about our own; young trees, mature trees, old trees…but it’s not the same thing, trees have an extraordinary potential longevity, they renew themselves, their buds are always young. It doesn’t matter how old they are.

A tree dies from external factors long before there can be a decline due to its age. That is why the oldest trees in nature are examples to be studied, the ones with the greatest capacity for adaptation and resistance. They are the ones that have managed to survive the changes in an ever-changing world.

Otras publicaciones

Tokonoma Morioka

Hoy tenemos a la Stewartia en el Tokonoma. Está mejor que nunca, en ese momento en el que luce su estructura y ya pueden verse sus brotes dorados. La gente se para, le hace fotos, me pregunta si es “de verdad”. Surgen conversaciones en torno a ella, la especie, su madera anaranjada, su origen…

Para completar el homenaje a la Stewartia, (porque eso hacemos al distinguir un árbol y colocarlo en el tokonoma) tenemos expuesta una fotografía que le hizo Andrea Savini desde arriba. Así todo el espacio de entrada está dedicado a ella.

De pronto pienso en la librería de Morioka Shoten del barrio de Ginza en Tokio, que se hizo famosa hace unos años por el concepto “una estancia un libro” .En su librería cada semana hay un solo libro y todo gira en torno a él. La idea de Morioka es dar protagonismo a una obra y promover el diálogo entre esta y su público. Si en el sector editorial es algo revolucionario por la cantidad de oferta y novedades que se apilan en las librerías, en cualquier colección expuesta es una idea interesante para distinguir una de sus obras.

Con este bonito concepto y con el año, empezamos con la Stewartia nuestro “una estancia un árbol” del mes.

Today we have the Stewartia in the Tokonoma. It is better than ever, at that moment when it is showing its structure and you can already see its golden buds. People stop, take pictures, ask me if it is ‘real’. Conversations arise around it, the species, its orange bark, its origin…

To complete the homage to the Stewartia, (because that is what we do when we distinguish a tree and place it in the tokonoma) we have on display a photograph that Andrea Savini took of it from above. So the whole of the entrance space is dedicated to it.

Suddenly I think of the Morioka Shoten bookshop in Tokyo’s Ginza district, which became famous a few years ago for its ‘a single room, a single book’ concept, where every week there is a single book at the shop and everything revolves around it. Morioka’s idea is to give prominence to a work and promote dialogue between it and its audience. If in the publishing sector it is something revolutionary due to the amount of offer and novelties that pile up in the bookshops, in any collection on display it is an interesting idea to distinguish one of the works.

With this nice concept and with the beginning of the year, we start with the Stewartia our “a single room a single tree” of the month.

Otras publicaciones

El anden 9 y 3/4/Platform 9 and 3/4

Seguimos inmersos en la magia de estos días, El tiempo queda suspendido, leo en alguna parte que es un fenómeno parecido al del andén 9 y ¾ de Harry Potter; doblas a toda carrera la esquina del día 25 y el tiempo se para.

Entramos en un tiempo distinto, ralentizado. Los árboles parecen contagiados por esa magia, como si estuvieran congelados (hoy igual lo están).

Los árboles duermen en el jardín, al parecer un estudio ha demostrado que cuando descansan cambian su postura; me fijo en ellos, las ramas parecen más bajas, los troncos algo más curvados…el tiempo perfecto para descansar, estos días no hay que producir nada.

.Solo, en la noche, el pino habla con su voz de luna…

«a los pinos el viento»

Luis Vallejo

We are still immersed in the magic of these days. Time is suspended, I read somewhere that it is a phenomenon similar to Harry Potter’s Platform 9 and ¾; you rush into the 25th and suddenly time stops..

We enter a different time, one that slows down. The trees seem to be influenced by that magic, as if they were frozen (today they might as well be).

The trees sleep in the garden, apparently a study has shown that when they rest they change their posture; I look at them, the branches seem lower, the trunks a little more curved… the perfect time to rest, these days there is nothing to produce.

Alone, in the night, the pine speaks its moon´s voice…

«The Wind among the Leaves»

Luis Vallejo